Background

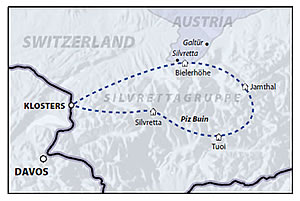

I have been doing day hikes and an occasional trek in the Alps and the Pyrenees and in Provence for over fifteen years. Three years ago we took a week hike around the highest Alp – Mont Blanc – going with a French group of twelve hikers, a registered Alpine guide, and a mule. More recently I trekked around the Monte Rosa – the second highest Alp – beginning in Zermatt, going south through steep Italian passes and valleys, and returning to Switzerland in the ski village of Saas-Fee. When the opportunity to hike around the Piz Buin on glaciers this July with a Swiss group presented itself, I could not resist this five day trip. I was able to leave Houston on a Saturday morning, fly to Zurich, take the train to Klosters, Switzerland, the village of departure, hike the glaciers for five days, and return to Houston on the following Saturday. I saw “a lot of real estate” in those five days, although much of it was under many feet of glacier ice and snow.

The Alpine Huts

Hiking considerable distances in the Alps is possible because of the Alpine Clubs of France, Switzerland, Germany, and Italy, which are national organizations maintaining cabins or huts at high altitudes for the benefit of their members and the general hiking public. Originally one room refuges from cold and storms, this hut system has grown into an immense network of small lodging facilities, most of which are in remote locations in the “high country.”

Sleeping is dormitory style – your carry your own light cotton sleep sack – and the hut supplies the mattress, pillow and blanket, and either a bunk bed (sometimes stacked three-high) or a sleeping platform where as many as 40 people may sleep in one room. In spite of what one might think, the deep and pleasant fatigue from a day of hiking almost always ensures a good night’s sleep.

To sleep overnight in the mountains in the United States usually requires the hiker to carry a back-breaking combination of sleeping bag, food, stove, tent, pots and pans, and many other items not necessary in the Alps, thanks to the huts.

Generally speaking, open camping is forbidden in the Alps. The huts provide a hot evening meal and breakfast, and there is usually a drying room available for damp clothing and boots. In addition, there is always beer and wine, not to mention schnapps, for those whose joints need a little anesthesia after a 6-9 hour day of strenuous exercise.

Some huts have hot water and showers, and some do not. Some huts are so remote that they were built by helicopter-transported materials and they are supplied with victuals by helicopters. Overnight with two meals in the huts costs in the range of $35-$65 per night. The main advantage of the huts is that due to their high altitude locations, the hiker – once up at altitude – can stay at altitude without having to go back down to a remote valley at the end of each day.

Meals are simple but hearty, and lean towards the high carbohydrate intake needed after hours of exertion at altitude. A large bowl of lentil soup (extra helpings available), followed by chopped cabbage and radicchio salad, followed by pasta and cheese, or by well-flavored polenta, or by beef paprikash: such are sample meals in the huts. Some huts feed 50 people + off a residential size four burner stove, and the burners are fired by…wood. The huts are usually managed by a husband and wife team, called Guardians. The Guardians are in the high country for the entire summer season and work hard and non-stop. Some huts are open all year round, and cater to cross-country and trekking skiers in the winter, but many are open only mid-June to mid-October to hikers when the high Alps are relatively snow free. Many huts are destinations for lunch or picnics on sunny days from day hikers coming up from the valleys below.

The huts have their own set of rules, etiquette, and common courtesies: shoes off at the front door, and slip into provided sandals; quiet after 9:00 PM (you are probably asleep by that time anyway); eat soup, salad, and main course out of the same bowl – dishwashing water and labor is scarce in the huts; bus your own table, taking your dirty eating utensils from the table and placing them in the window into the small kitchen; and, perhaps the most important: never allow your guide to pay for his own drinks!

The hikers, who are usually in groups, eat, drink, walk, socialize, and sleep with their fellow hikers for the entire period of time they are in the high country, so many friendships are made.

The Alpine Trails

The trails which wind all through the Alps are generally well-maintained and well- marked by the respective Alpine Club volunteers, who give of their personal time to keep up the huts and the trails. Stone cairns are erected in high areas where a sudden storm might dump just enough snow to obscure the trail or the painted blazes which mark it. Notwithstanding the best efforts to mark the trails, there is still plenty of opportunity to get lost, especially when walking on glaciers or on huge fields of loose stones, which are always moving and which are difficult to mark.

The Group

After enrolling with Mountain Reality of Andermatt, Switzerland (my second trek with them), I was instructed to meet my guide and group at 1:00 PM Monday at the Klosters train station. Klosters is the next village over from Davos. An equipment list was provided, as was the opportunity to rent an ice ax, crampons, and a safety harness, all needed for glacier trekking.

The group turned out to be small – three Swiss hikers, a guide from the Swiss Mountain Guide Association…and one Texan. A van took us to the trailhead at the end of the valley above Klosters, where the fun began. A steep hike of two and a half hours took us up to the Silvretta Haus hut, our first overnight hut. The weather was socked-in misty, with low visibility. A hot meal was welcome, and we went early to bed to prepare for a long day on the glacier, which was scheduled to begin early. Before retiring, we were required to register in the Hut Book. In scanning back through early 2005 and into 2004 I found many nationalities represented, but no Americans-let alone Texans!

The second day of hiking found the Silvretta Hut still in the middle of a white-out. We loaded up our packs, and set out into the white. After ascending on a rocky moonscape path for about fortyfive minutes, our guide halted us at the lowest tongue of the glacier, and began roping us up. As we began our careful way up the glacier, because of the weather conditions, our guide Hansjorg had to rely on a handheld GPS (global positioning system) to stay on the correct bearing, since sky and earth were all the same white, with no visible horizon. With difficulty we kept the rope just tight enough between each hiker, without disturbing the pace of the guide.

At one point in the white, I begin hearing a rumbling noise, increasing in intensity. Suddenly I realized I was walking right over a coursing river – under the glacier I was walking on! Eventually the sun broke through the clouds, right as we reached the pass into the next valley. Our descent back through the treeline to our second hut, the Chamanna Tuoi, was breathtakingly beautiful.

The following day was another seven and one-half hours of beautiful glacier hiking, this time in full sunshine. Even with a t-shirt on we were sweating heavily, as each footstep in the steep snow consumed at least twice as much energy as if we were walking on solid rock. Today’s glacier snow, in spite of the sunshine, remained frozen, and as we walked in our roped up line, the guide, in the lead, had to chop each foothold with his “Pickel,” or ice ax, as we worked our way slowly and precariously up. We reached the saddle of snow which was the pass into the Jamthal (Jam Valley of Austria) at noon, after five straight hours of uphill climbing. We noticed all too well the altitude, since the higher we went the more concentration it took to match our breathing to the pace set by the guide.

As we crested the saddle of snow, still roped up, and began our careful descent, slogging down through a three foot snow cover on the glacier, our guide changed the order on the rope. He moved to the rear, and asked Judith, a fit and experienced hiker, to take the lead, and to probe carefully for crevasses. We were reminded once again to keep the ropes taught, so in the event one of us fell, the time before the jerk on the rope connected to the rest of us would be short, and the falling climber would not have time to tumble very deeply. Suddenly Judith made a floundering movement and then, prone on the snow, scrambled to her feet, warning the next climber, Jurg, of a crevasse. Jurg and the rest of us stopped, while he sat on one side of the two foot wide crevasse and put his feet on the other side. He yelled Expedition guide Hansjorg at Judith to pull, and soon he was upright on the other side. As each of us performed the same maneuver, the snow masking the crevasse tumbled down, leaving the apparent gap larger and larger.

Another heart-stopping event occurred shortly after passing over the summit. We came to a halt at a long and steep rock field, where tens of thousands of stones, all roughly the size of a basketball, lay balanced one on another. Our guide preceded us and began kicking the loosest of the stones ahead and down the rock slide, to try to prepare a less dangerous route for us. One large stone he dislodged took an unpredictable turn once he had given it a shove with his leg, and it bounced as if it was going to fall on his other leg. He instinctively rolled, but not before the heavy stone snapped his metal walking stick as if it were a toothpick. The four of us stood there horrified at the thought of what we would have done had his leg been snapped in two at that remote high altitude location.

While at the ‘top of the world,’ which we achieved several times, the immensity of the Alpine “Gipfels,” or peaks, stretching out for perhaps fifty miles in every direction, was starkly beautiful. So far above the vegetation line, these vistas were in black and white, not color, which mostly vertical and jagged protrusions jutting up from and through the myriad of glacier fields for as far as the eye could see. Every now and then a jet contrail would appear and linger across the blue: Milan-Paris? Turin-Geneva? Rome-Amsterdam? Although the area we were in had paths connecting the different destinations and huts, on only one day did we pass any other group. Solitude, beauty, and quiet were the adjectives which described our five days in the high Alps. The long descent to the Jamthalhutte was beautiful, and the hut, far below, was visible to us for about two hours until we could reach it.

The following morning, we had a choice of routes: another over-the-top glacier hike, or the valley route, through the Austrian ski village of Galtur. Galtur was in the news a few years back when a massive avalanche took out several homes on the fringes of the village, costing several lives.

Three of us took the twelve mile valley hike, and the remaining hiker in our group took the high path with the guide. We walked through a deep valley along roaring glacier-melt streams, and shared the path with a herd of Austrian milch-cows, with their resonant clanging bells tied securely around their necks. At two points in the valley descent we passed lowceilinged stone dairy farms with signs in front advertising fresh butter and cheese.

In Galtur we connected with the Post Bus to Bielerhohe, on the Silvretta Lake, and then walked down to our last hut, the Madlener Haus. Once our entire group was reunited, we celebrated our last night together with perhaps a little too much schnapps and beer, so that the next morning we started off a little more groggy than usual. Friday morning saw us on yet another five hour pull to the summit, which is called Rota Furka, through rock and snow fields, where Hansjorg once more had to chop steps for us across steep and frozen slopes of snow. Before reaching the snow and ice, however, we wandered through several micro-climates, including a sort of Alpine wetland, where we spotted leaping frogs, tadpoles, rabbits, marmots, and various butterflies…all on wet terrain which was frozen at least half the year and covered with countless meters of snow. And yet in the sunny summertime, life re-emerged.

Almost any trip to any section of the Alps will confirm the earth’s rising temperatures, as glaciers continue to shrink from year to year. Hansjorg told us that since the first time he saw the Rhone Glacier in 1972 it has shrunk in height by 150 feet! This immense shrinkage in only thirtythree years of this mighty glacier is ominous for not only the Rhone but for all rivers worldwide which spring from glacial melting. The glacier is a primary source for the water which keeps the river flowing year ‘round, even in drier seasons.

At last we reached the final summit, and began our descent to Klosters, passing by the Silvretta Hut, where we had spent the first night. The descent involved very narrow pathways along a steep slope, with mountain on the right and eternity on the left. One of the two ladies in our group became petrified with fear and had to be coaxed footstep by footstep by the guide until the trail became more easily negotiable.

Finally we arrived at the hut, had a short picnic of dried sausage, cheese, and a bowl of warm soup. We then began our final two hour descent back to Klosters, along the path we had taken up only five days before. The van was waiting for us at the trailhead to take us back to the train station, where goodbyes were exchanged, and our group dissolved back into the real world as quickly as it had formed earlier in the week, on the same quai of the same station.

The Equipment

We hiked with forty liter packs, in which we carried clothes and toilet articles necessary for five days. With practice the hiker learns how to minimize “necessities,” and the difference between a pack which weighs eighteen pounds and one which weighs twenty-five becomes more noticeable with each day of hiking, especially at altitude. Good hiking boots, sunscreen, a fleece, rainpants, and a waterproof windbreaker round out the list of most necessary items.

The Conditioning

The hiker must be fit to hike at high altitudes carrying a 20 lb + pack. Before treks, I climb stairs daily in my office building, workout on an elliptical cross-country machine, and do two hour/eight mile hikes every other day in the neighborhood, with and without a pack. Training must condition muscles to ascend, to descend, and to walk laterally considerable distances, since it is not unusual to be on the mountains for up to nine hours on a given day.

I never want to let my fellow hikers down physically, especially in a remote location. Besides, on all of the treks I have taken in Europe with groups. I have always been the only Americans in the group. We don’t want to be unfit.

The Organizers - Cost and Schedules

There are numerous companies which organize hikes in the Alps. We have always chosen the European ones, since we feel they know their own territory best, and since they are always the most affordable. We paid about $500 per person for the Tour du Mont Blanc, about $700 for the Tour du Monte Rosa, and about $750 for the recent glacier trek around the Piz Buin. Without exception the European fellow hikers have been friendly and fun, since everyone is drawn together by the same love of natural beauty, fresh air, exercise, and the towering mountain peaks.

We have used with success Bergschule Uri-Mountain Reality in Andermatt, Switzerland, and Echaillon, a French company located near Briancon. Both can easily be found on the internet. If you have trouble reading their web sites, friendly responses to queries by email will be answered in English. Both have extensive catalogs of hikes, which include many itineraries in the Alps, the Dolomites, and even Nepal and the Andes. Normally the hikes are available from late June through October, and each company has a winter schedule of off-piste ski adventures. There are American “adventure” companies which run similar tours, but we have found them to be roughly four times as expensive as the European companies.

Suggested Reading

There are many books available on hiking in Europe, and they can be found at amazon.com, REI and other outdoors stores, and at the bookstore. One of the very best – one which has stood the test of time – can be ordered from amazon and is called Scrambles Amongst the Alps, by E. Whymper. Whymper was an Englishman who pioneered hiking, climbing and summiting the Alps, and he was the first to climb the Matterhorn.

Download a copy of this article as a pdf (more images!). Download now

Further Questions?

Feel free to call Ray Hankamer at Hankamer & Associates – 713.922.8075 or email. I will be happy to share with you any experience I have from hiking and travel in Europe.